From Roman classics to British tabloids, humans have long celebrated the curious and remarkable ability of birds to imitate the sounds of humans and other animals. A recent surge of research is revealing how and why birds use vocal mimicry to further their own interests, as we discuss in Biological Reviews.

Far from being merely a biological curiosity, it appears that vocal mimicry plays a more central role in the lives of birds than we have given them credit for.

Most birds communicate using vocalisations unique to their own kind, but a diverse group of species from around the globe regularly imitate the sounds of other animals, including sounds we produce ourselves.

In Australia, these avian “mimics” are all around us. On a stroll in the Blue Mountains, for example, you can expect to encounter several of them, including arguably the world’s most famous vocal mimic, the superb lyrebird, along with lesser-known mimics like the silvereye, the satin bowerbird, the mistletoebird, the yellow-throated scrubwren, and the feisty brown thornbill.

Even the Australian magpie – better known for swooping cyclists or pinching food from picnics – occasionally quietly imitates other species of bird.

What sounds do birds imitate?

Avian vocal mimics often imitate the songs and calls of other species of bird, but they can also imitate the sounds of mammals (such as growls of yellow-bellied gliders), the hiss of snakes, and the wing-beats of birds flying by.

Birds can imitate sounds of human origin but recordings of these are rare, and many reports may come from observations of captive individuals, or may be misinterpretations of natural sounds.

The mimetic feats of birds can be gobsmacking. A single superb lyrebird can imitate more than one bird calling at the same time. The 7 gram brown thornbill can imitate the song of the predatory pied currawong, a bird more than 40 times it size. And the marsh warbler is versatile in the extreme, and is known to imitate more than 200 species of African and European birds without ever seeming to sing its own tune.

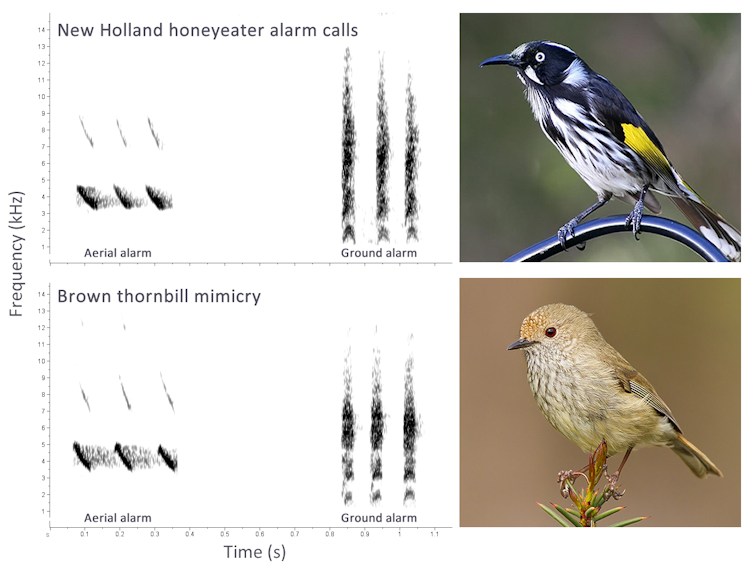

A single species may change its mimicry depending on the context. When confronted with a taxidermy owl placed on the ground, brown thornbills mimic the alarm calls that other bird species make in response to predators on the ground (listen here).

However, when a fibreglass model of a sparrowhawk is thrown over the top of them, brown thornbills mimic the alarm calls that other bird species make in response to predators in the air (listen here).

This tiny mimic, therefore, can communicate about different types of danger in several different avian “languages”.

Owl chicks that sound like rattlesnakes

Through vocal mimicry, an avian mimic can manipulate the behaviour of others for its own benefit. It seems that birds use vocal mimicry sometimes to deceive and sometimes to impress.

Deceptive vocal mimicry can allow birds to obtain food that they are not entitled to. The fork-tailed drongo of Africa mimics other species’ alarm calls to “cry wolf”, falsely signalling the impending attack of a predatory hawk. In the ensuing mayhem, the drongo steals food that has been abandoned by fleeing meerkats and pied babblers.

In Australia, the Horsfield’s bronze-cuckoo lays its eggs in the nests of superb fairy-wrens and other species, which then raise the cuckoo chick as one of their own. However, fairy-wrens have evolved a set of defences against cuckoos and may abandon a nest if they think something is amiss. The cuckoo chick ensures its survival by mimicking the begging calls of the fairy-wren’s own young.

Surprisingly, the cuckoo chick is a versatile mimic. If the chick hatches in the nest of a buff-rumped thornbill, then the cuckoo mimics the sound of buff-rumped thornbill nestlings. The cunning cuckoo tunes its mimetic begging call to the sound that elicits the most food from its host, allowing it to parasitise more than one species.

Other species seem to use vocal mimicry to deceive predators and so avoid being eaten themselves.

In the Americas, the burrowing owl lays its eggs in tunnels in the ground where the young are vulnerable predators. However, when disturbed, burrowing owl chicks produce a distinctive call that is strangely similar to the rattle of a rattlesnake. Experiments have shown that this mimetic rattle deters other animals from entering burrows.

There are several other reports of incubating adults or nestling birds producing snake-like hiss calls when disturbed. It has also been suggested that nestlings of an American woodpecker, the northern flicker, imitate the buzz of a hive of bees in order to survive an encounter with a predator.

Seduction songs

Some of the most spectacular examples of avian vocal mimicry are of birds that imitate multiple species during sexual display. Such species include the two species of lyrebird of Australia, tooth-billed bowerbirds from Queensland, and the northern mockingbird of North America.

During the breeding season, the males of these species sing long, loud bouts of the imitations of the songs and calls of other birds, which they deliver from song perches or carefully constructed display platforms.

Such mimicry can be extraordinary, both for the sheer number of different sounds mimicked and for its accuracy. The superb lyrebird, for example, can produce mimicry to a level of accuracy that even the bird it imitates is confused.

Currently, the best evidence that birds use vocal mimicry to entice mates comes from studies of satin bowerbirds, found in eastern Australia.

Satin bowerbirds attract females with an elaborate display involving a decorative bower and a performance that includes vocal mimicry. Females prefer to mate with males that can accurately mimic a large number of different species of bird. Perhaps female bowerbirds can assess the male’s genetic quality through his prowess in vocal mimicry.

Australia has many avian vocal mimics, leading the early 20th century writer Alec Chisholm to suggest that this continent might have more than its fair share.

Indeed it is likely that some Australian species of avian mimics sometimes mimic each other. An avian soundscape populated by mimics is fascinating to contemplate.

The next time you go for a bushwalk, you might want to listen back to the birds you come across – are they honestly singing their own tune, or have they stolen someone else’s?![]()

Anastasia Dalziell, Postdoctoral Associate, Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Cornell University and Justin A. Welbergen, Senior Lecturer – Animal Ecology, Western Sydney University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.